3I/ATLAS is the third known interstellar object to enter our solar system, after ‘Oumuamua (2017) and 2I/Borisov (2019). First detected in mid-2025, it’s a fast-moving, hyperbolic visitor: an icy body traveling on a trajectory that originated outside our solar system and will leave it again after its solar flyby.

Based on its coma and tail-like activity, astronomers officially classify it as a comet. That label hides more than it reveals because 3I/ATLAS is behaving like no comet we’ve ever seen. Yet mainstream voices in astrophysics continue to declare — with confidence and little curiosity — that 3I/ATLAS is “just a comet.”

Curiously, that might be the least scientific take of all.

The Sunward Anti‑Tail That Shouldn’t Exist

Let’s start with the most glaring anomaly: the anti‑tail.

Yes, astronomers are familiar with the appearance of sunward‑pointing tails when a comet passes through the plane of its own debris trail. That phenomenon is well understood. It’s a line‑of‑sight illusion caused by geometry.

That is not what 3I/ATLAS is doing. The anti‑tail associated with 3I/ATLAS is:

- Physically extended, not a projection artifact

- Directed straight toward the Sun, not merely offset

- Persisting over an enormous distance that appears to exceed the Earth–Moon separation

Under normal physics, gas sublimated from the sunward side of a comet should be pushed away from the Sun by radiation pressure and the solar wind. For material to remain coherently sunward over that scale, it cannot be fine dust or vapor. It would need to consist of substantial grains or structured ejecta.

We have never, ever, observed a natural comet producing a sustained sunward structure like this.

Calling it “an anti‑tail” and moving on doesn’t explain the mechanism. It just renames the problem.

Three Jets, Spaced 120 Degrees Apart

Then there are the jets.

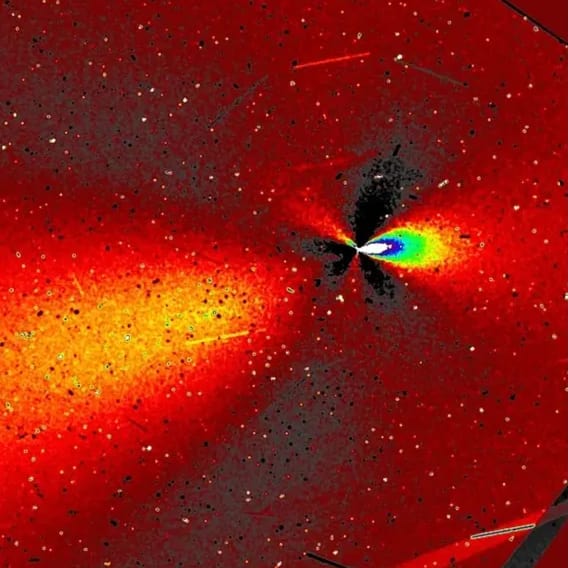

Images of 3I/ATLAS show three prominent jets (see above), spaced at roughly 120‑degree intervals around the nucleus. That spacing is mathematically precise. It’s not random. It’s not chaotic.

Three evenly spaced thrust points are exactly what you would design if you wanted:

- rotational stability

- controlled orientation

- minimal torque imbalance

Comets do have jets, but they’re typically irregular, asymmetric, and transient, tied to patchy volatile deposits on an uneven nucleus. Symmetry like this is rare to the point of being remarkable.

Once again, the response has been to say, “Comets can have multiple jets.” That statement is true, and completely misses the point.

The issue isn’t multiple jets. The issue is geometric regularity.

Hexagons, Saturn, and the Hexmen

This is where fiction and observation collide.

In my novel Infernum, Commodore Ahrens argues that the hexagonal weather pattern at Saturn’s north pole cannot be natural. His reasoning is simple: nature does not abruptly change wind direction at exact 120‑degree interior angles to form a perfect hexagon. The structure is too precise, too stable, too clean.

In the novel, this becomes evidence of an alien species—the Hexmen—whose calling card is hexagonal geometry. They leave it behind wherever they intervene: Saturn, the Moon, elsewhere.

That argument was fictional. But the logic behind it was not.

And now we’re staring at an interstellar object exhibiting threefold symmetry, 120‑degree spacing, and sunward‑directed structures that defy our existing physical models. And we’re told to ignore the geometry.

At some point, pattern recognition stops being superstition and starts being analysis.

A Curious Encounter with Jupiter’s Hill Sphere

3I/ATLAS is not just passing through the solar system at random. Its trajectory will take it near Jupiter’s Hill radius, the region where Jupiter’s gravity dominates over the Sun’s.

Why does this matter?

Because objects interacting with a planet’s Hill sphere can:

- shed material into stable or semi‑stable orbits

- deposit debris into Lagrange points, where gravitational forces balance

- leave behind companions or fragments that persist long after the primary body exits

Lagrange points, in particular, are useful because they offer gravitationally balanced regions where objects can essentially “park” with minimal energy expenditure. We humans take advantage of this ourselves—the James Webb Space Telescope is stationed at Earth–Sun L2, a Lagrange point that allows it to maintain a relatively stable position with minimal course correction, always aligned with both the Earth and the Sun.

So if you were, say, dropping off a payload designed to stick around quietly for decades, Lagrange points would be the perfect drop zones.

Again: I am not claiming intent. I am saying the geometry and timing are interesting enough that dismissing them outright is intellectually lazy.

When “Just a Comet” Becomes an Article of Faith

What’s most striking about the reaction to 3I/ATLAS is not skepticism—skepticism is healthy—but dogmatism.

The conclusion (“it’s just a comet”) appears to precede the explanation. Every anomaly is then forced into that conclusion, rather than the conclusion being allowed to evolve from the observations.

Science doesn’t advance by declaring anomalies boring.

3I/ATLAS presents:

- a sustained sunward structure we’ve never seen before

- geometrically regular jets

- a trajectory that brushes a major gravitational staging area

- an origin outside our solar system

Each of these alone would be noteworthy. Taken together, they deserve more than a shrug.

Maybe 3I/ATLAS is natural. Maybe there’s a physical mechanism we haven’t yet modeled. But pretending this object behaves like an ordinary comet when it plainly does not is not skepticism.

It’s denial.

And history has not been kind to scientists who insisted the universe behave only in ways they were already comfortable with.

Jayson Adams is a technology entrepreneur, artist, and the award-winning and best-selling author of two science fiction thrillers, Ares and Infernum. You can see more at www.jaysonadams.com.